1951 - 2020

Born in Chernivtsi, Ukraine, Shimon Okshteyn was a graduate of the Mitrofan Grekov Art College in Odessa, Ukraine. He lived and worked in the USA since 1980.

Since the early days in his new country, Okshteyn was a keen and sensitive observer of the external environment voraciously absorbing it. He did not hold on to the past, but took the best from it making use of art historical references, playfully reinvigorating elements from the Renaissance, Baroque and social realism, as well as German expressionism, linking these to the present in a highly astute and distinctive idiom. He expressed his new reality in his work balancing between the high and the low, public and private with a characteristic style that shifted between abstraction and figurative. He was the barometer of time who defined where the artistic interest of the epoch was moving.

In his varied and diverse approaches to making art - installations, paintings and sculpture his methodology was consistent.

The use of materials in his work was calculated. There may not always be similarities between the different bodies of work. Each one often consisted of works in diverse mediums grouped around specific themes offering a colorful first impression, but on closer inspection revealing multiple layers of meaning and intricate narratives. His practice came from the concept of difference and appropriation. It explored the varying relationships between popular culture and fine art. In the current climate where many believe history has no relevance, he found himself continually returning to those aspects that still strongly resonate with us today by meticulously preserving disappearing objects for posterity or reproducing excerpts of iconic works of art and inserting them into contemporary context.

He was often looking for avenues of the unexpected provoking a participant to new and perhaps unexplored territories.

Okshteyn works have been featured in solo exhibitions at such institutions as the G.W.V. Smith Museum, Springfield, MA (1987), Grinnell College Museum of Art, Grinnell, IA (2002) The State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia (2007), and Memorial Art Gallery, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY, companion show to Natura Morta: Still-Life Painting and the Medici Collections (2007). His works were included in New Acquisitions: Brooklyn Museum of Art (2001), Approaching Objects: Works from the Whitney Museum Permanent Collection at the Whitney Museum of American Art (2003), Extra-Ordinary: Everyday Object in American Art, New York State Museum, Albany, NY (2005), Leaded: The Materiality and Metamorphosis of Graphite, traveling exhibition: University of Richmond Museum, Richmond, VA, Memorial Art Gallery, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY, Palmer Museum of Art, University Park, PA, Salina Art Center, Salina, KS (2007-2009), Here’s the Thing: The Single Object Still Life, Katonah Museum of Art, Katonah, NY, (2008). In 2010 several of Okshteyn works were on view at the Galerie Rudolfinum and Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague in the Decadence Now! Visions of Excess exhibition curated by Otto M. Urban along with such notable artists as Jeff Koons, Gilbert and George and Chapman Brothers. In 2014 several of his installations from the permanent collection of the Nasher Museum at Duke University were on view at Duke in the summer blockbuster show Connecting and Curating organized by the Rauschenberg Foundation and curated by Kristine Stiles.

2009 Inducted into the Russian Academy of Arts

2001 Visiting Artist, Washington University, Department of Printmaking, St. Louis, USA

1997 Award, Biennale Internazionale Dell'arte Contemporanea Florence, Italy

When I first spoke to Shimon Okshteyn about how I planned to discuss his art, I happened to mention, if only as an opening gambit, that I had already known of a number of other artists or writers of talent who came originally from his native city of Chernovitz or from other cities of the formally Austro-Hungarian provinces of Bukovina and Galicia which after World War I, were Romanian or Polish before ultimately becoming parts of the Soviet Republic of Ukraine. Very modestly, Okshteyn answered me by remarking that the general public in the world’s major intellectual and artistic centers, such as New York, Moscow, Paris or London, generally assumes that no art or literature of real significance can be produced by those who hail from the more distant provincial centers that gravitate around them like the many satellites around some great planet.

I then remonstrated that Ezra Pound was but one of the many major American writers who, like Mark Twain too, came originally from the Mississippi Valley or even more distant Idaho and whose works display little influence of Manhattan. This led me to add that I have personally known at least two outstanding writers who happen also to have been born in Chernovitz, though in the years when it was still the capital of one of the Romania’s northenmost and more recently acquired provinces: Paul Celan, who is now widely claimed to have been German literature’s greatest postwar poet and Ahron Appelfeld, the equally remarkable Hebrew novelist and story-writer. To these two names of personal acquaintances I might have well have added those of a number of distinguished writers or artists whose works I have long known and admired and who also came from Chernovitz or from other such cities of Bukovina or Galicia: the German poet Rose Auslaender, likewise a native of Chernowitz, the Hebrew poet Dan Pagis, who was born in a smaller town of Bukovina, the great Austrian novelist Joseph Roth, originally a native of Galicia, the outstanding turn-of-the-century graphic artist E.M. Lilien, who was born in Drohobycz, made a great career in Germany and became one of the founders of Jerusalem’s prestigious Bezalel Academy of Fine Arts, the hauntingly strange Polish story-teller and draftsman Bruno Schulz, likewise a native of Drohobycz, and the Galician-born “School of Paris” painters Aberdam and Arthur Kolnik, of whom the last-named was at one time known as “the Chagall of Galicia”

Such are indeed but a few of the more remarkable literary or artistic talents that have arisen from these distant and all too often despised provinces of Eastern Europe and whose names come to my mind as I consider how much of them in turn has contributed to the intellectual life of Austria, Germany, Poland or France and now, in the case of Shimon Okshteyn, to that of the United States. They all happen moreover to be of strictly Jewish origin, although I might also add, to this long list, the names of two German-language writers recruited from the lower ranks of the Austro-Hungarian nobility of these provinces: the novelist and story-writer Leopold von Sacher-Masoch, who was born in the Galician city Lemberg (Lvov), where his father was the Austrian Chef of Police, and the satirical writer Gregor von Rezzori, whose first two books offered his German readers humorously nostalgic description of his youth spent in the multi-racial and multi-cultural environment of Chernowitz.

In several New York subway station, a new poster for Virginia Slims already looks suspiciously like a plagiarism inspired by Okshteyn’s paintings of such elegantly sinister chain-smoking young women. But advertising art has constantly, in recent decades, sought inspiration from the works of such major contemporary artists as Salvador Daly and Andy Warhol, so that Shimon Okshteyn thus finds himself already in the company of those very few masters of contemporary art whose sardonic comments on our economy of consumption and of what Thorsten Veblen once called “conspicuous display” and “conspicuous waste” lend themselves readily to the more commercial art of advertising; and in this too there exists an ambiguity or an ambivalence that might deserve more ample critical evaluation.

___Edouard Roditi, “Shimon Okshteyn: An Innocent in America”, Los Angeles 1987

full text

Shimon Okshteyn brings a personalization of an intensity that American art has not seen since Joan Sloan’s paintings of New York and its women. The journey from Russia has been a hard one for Okshteyn, but it is by no means complete. When one views his work, one hopes it never will be, for he has brought from Russia a unique subject and a way of painting it that enriches the art of this country.

Richard Muhlberger, Director, G.W.V. Smith Art Museum, Springfield, MA

Okshteyn, separated by time and space from the Russian modernists of the twenties and leaving behind the French inspired academic approaches of expressionism, produces a different impression of life around him. He is like a tree, which is uprooted by forces beyond his control, the storms of our times; but his roots are strong, imbedded in his art, and transplanted, grows and gives fruit. He is an artist who gets stronger, his vision clear, a hidden intellectual who observes the world around him and shows it in his metamorphoses. He is not ethnic art, not Russian, nor local, but international in scope and understanding.

___Emil G. Schnorr, Conservator, G.W.V. Smith Art Museum, Springfield, MA

Some men are so made that for them women provide a constant spectacle. Shimon Okshteyn is such a man. And so it is that those women who contrive to reinforce their powers of seduction would inevitably attract the attention of a man who watches women and who is an artist! Besides, how can an artist worthy of that name not observe women? Have they not been since the beginning of time as much a lesson in the art of inciting the look of another, be it that of their own rivals, as in the art of using forms and colors. Thus Shimon Okshteyn looks at women. He looks at THESE women, but considers them not only as masters of the “art of behavior” about which so much has been said these past few years, or of the art of painting their faces, but as quite monstrous creatures who, in the theater of sexual attraction, unrelentingly play out the comedy of losing souls — their own and those of the ill-fated men or women who fall into their nets. Besides, do they merely play this comedy, or are they their first victims?

Whether they wear a mask or not and whether or not they are the first to fall victims to their own masquerade, those whom the artist is particularly eager to show us have in common that they are decked out in the various items of their seductress’s outfit just as knights in the Middle Ages wore their armor leaving no trace of the human beneath the metal, so these women show no trace of anything natural. And in the absence of any other armor they conspicuously brandish a long cigarette from which, as if by a miracle, the ash remains intact even though it is pointing slightly downwards. Wesselman also noticed how many great seductresses were at the same time heavy smokers, as if by this intense burning of tobacco they sought to establish a definite link with the smoldering log fires of witches as surely as with fires of Hell. But it is equally obvious that those long white cylinders they hold between their fingers or place between their lips fulfill among other roles a simulacrum of the virilities they meant to covet, threaten or challenge.

However that may be, as to the sociological or even symbolic truth of Shimon Okshteyn’s works, one cannot emphasize strongly enough how terrifying the beauty of these very modern sirens is used with cold efficiency and icy precision which about 50 years ago characterized such German artists as Otto Dix, Raderscheidt or Christian Schad of the Neue Sachlichkeit movement. Such comparison for my part is not intended as a reproach, far from it. Artists from the Weimar republic were also confronted with a profoundly demoralizing world which some among them thought to denounce by the impeccable precision of their style. In fact, they did more than that. Like Shimon Okshteyn today, they light up for us the depth of the human heart.

___José Pierre, Paris, March, 1985

Shimon Okshteyn, Satisfaction, 1984 included in "Witchcraft. The Library of Esoterica" hardcover, 520 pages book published by Taschen, 2021.

The same year that Rauschenberg painted Wild Strawberry Eclipse, the Ukrainian artist Shimon Okshteyn created There Are Many Forms But Few Classics(1988). The left side of the large, polished, steel diptych contains only the neon words of the title and its reflective surface that makes the viewer part of the picture, while the right side sports Okshteyn’s photorealistic painting of a “classical tire”, painted during the period when he was interested in depicting “classical objects like women’s lips, part of a shoe” and so on. As viewers’ reflections merge with the light from the neon title, they become part of the “many forms”, perhaps equally suggesting that people are, in their own ways, “classics”.

___Kristine Stiles, Curator, Rauschenberg: Collecting & Connecting, Nasher Museum at Duke University, Durham, NC

Installation view, Rauschenberg: Collecting & Connecting, Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina, 2014–15. Works pictured: Shimon Okshteyn, There are many forms but few classics, 1988; Robert Rauschenberg, Meditative March (Runt), 2007; Rauschenberg, Wild Strawberry Eclipse (Urban Bourbon), 1988. Photo by Peter Paul Geoffrion.

Installation view, Rauschenberg: Collecting & Connecting, Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina, 2014–15. Works pictured: Shimon Okshteyn, Armchair, 1995; (vitrine) Lia Perjovschi, Our Withheld Silences, 1989; Robert Rauschenberg, Untitled (Venetian), 1973; (vitrine) Rauschenberg, Untitled (Elemental Sculpture), ca. 1953; (partial) Bruce Conner, WHEEL COLLAGE, 1958; Nikolai Panitkov, Stuff Up the Hole, Stuff Up the Crack, 1987; Lyle Ashton Harris, Untitled (Oak Bluffs) from the series The Watering Hole, 1996; Rauschenberg, Olympic / Lady Borden (Cardboard), 1971. Photo by Peter Paul Geoffrion.

What makes Okshteyn special is to be able to take traditional means and shape an enormous change in scale: the pencil asked to do heavy carrying. And it works, the image becomes icon, its impact profound.

___ J. Bowyer Bell, Review Magazine

This is a new kind of Pop Art. Engaging, shocking and baffling. Okshteyn’s purpose is to focus the world around him through an intense engagement with these objects and let nothing distract him in their contemplation. He is after all pursuing an headlong, relentless and probably impossible task, but in this battle to represent, to illuminate this past, this history, his being undistracted is a gift to us all.

___Robert Sandelson, London

Shimon Okshteyn’s art has a hauntingly evocative quality that suggests nostalgia, captured moments, tender memories. With immense technical skill, he works in pencil and graphite, sometimes collage, as well as sculpture. As subject matter, hats and shoes and corsets of another era are depicted with rare finesse. Somehow, he is able to introduce an other-worldly quality to this work that often has the color and feel of early Daguerreotypes.

___Elaine Benson, Bridgehampton, NY

Okshteyn posses the technical virtuosity that had been the standard for measuring artistic greatness for centuries. Only in this century where technological means of standardized representation, (i.e. photography, etc.) have momentarily blinded the public eye to the value of representational painting and drawing, has realism as a genre fallen by the wayside. …Public opinion of art is coming full circle, and Shimon’s star — already well into the stratosphere — will continue its rise on the wave of respect for traditional technique and labor intensive rendering.

___ Renée Dahl, H Connoisseur

Okshteyn's still lifes—objects whose life has been stilled—not only explore the boundary between ordinary objects and poetic objects—non-art and found art—but between aesthetics and erotics.

___Donald Kuspit, New York City

What is it about the objects of Okshteyn’s preoccupation? The new show is full of exquisite portraiture of typewriters and alarm clocks, a telephone, a fan, and a table top juke box. In common, all of these machines are relatively recent antiques — twenties through fifties — a faded quality they share with Okshteyn’s earlier fascination with the apparatus of tailoring, with decaying dressmaker’s dummies, hat blocks, thimbles, spools of thread and strange seventies platform shoes.

Both of these collections are of everyday objects of vanished worlds. These worlds share an innocence that registers in the visibility of their appliances. Both dressmaking and small domestic appliance technology are hands-on mechanical, foregrounding their physics. Differing from the automated technology of today that conceals its working either in static circuitry or under a blanding cowl, they require human energy and engagement. Is it pushing too far to say that this reflects Okshteyn’s painterly position, his simultaneous exultation of craft and precision and his demand that art serves memory.

One hesitates to invoke biography as a tool of criticism but Okshteyn wears it on his sleeve. A Russian, Jewish immigrant to the U.S., Okshteyn makes work that is very much about the lines between nostalgia and loss, depictions of a kind of vanished paradise. Here is another innocence of this machinery, its ability to build a picture of a world that is no more. The garment trades were the preeminent first generation employers of Jewish workers new to New York. The antique machines likewise depict a vanished environment, an age before technology had acquired its Frankenstein sting, when the idea of a “labor saving device” seemed truly to offer freedom.

In his tinged fascination with bygone machinery, Okshteyn practices something like the inverse of constructivism. Focused on the near past instead of the near future, his art suggests both a loss of faith with the heroic project of Soviet art and longing for other, more directly representative media. That he chooses to represent the zygotes of technology instead of its grand elaboration is not ironical but cautionary and gentle, portraits of machinery uncorrupted, save by time. His choice insistently focuses on the thing itself, an implicit critique of artistic strategies lost in the conceptual and unable to produce objects of satisfying complexity.

Okshteyn’s prodigious technique is part of this. And it is prodigious: Shimon gave me some images as aides memoir and I sweat bullet that I wouldn’t be able to tell if they were photos of the originals or the works themselves. Of course I could tell and this dimension of difference could also see clearly what the work is about. Mimesis is a calibration, a calibration, a measurement of the relationship between passion and object. For Okshteyn, these objects — because they are historical, because they have been used, because they have been places —- have the imprint of life; no less, in their way, than a portrait of a human subject. In choosing these humble objects, Shimon Okshteyn performs a reanimation, bringing them to life with the manner of hand and light.

___Michael Sorkin, Shimon Okshteyn: Aging Icons, NYC

Shimon Okshteyn’s hyper-real new black and white graphite drawings on canvas of such everyday objects as freshly packaged pasta from Balducci’s and a sevety-five watt light bulb are remarkable for depicting both the object and the photograph of the object which serves as the formal subject of the drawing. His handling of light in its encounter with transparency — the glass of the bulb, the plastic of the pasta package — is particularly marvelous.

These drawings are also highly autobiographical. The range of subjects Okshteyn has painted over the years — from old hats and clothing to out-of-date appliances to high-class comestibles — reveal his own unfolding interaction with life in the United States after his years in the Soviet Union.

___ Ivan Karp, OK Harris Works of Art, NYC

Yet, Extra-Ordinary: The Everyday Object in American Art, which is the 13th install- ment in the Bank of America (formerly Fleet Bank) Great Art series at the State Museum, is still cause for celebration. Incorporating just over 40 pieces by 22 artists, the earliest a 1938 Man Ray ink drawing and the latest a 2000 graphite on canvas by Shimon Okshteyn, the show is a treasure trove of (mostly) witty and masterful works by some of the best artists of recent times, all culled from the vast holdings of New York City's Whitney Museum.

….For many visitors to the museum, this will be their first experience of this kind of art. But, for me, the show was more a case of revisiting numerous dear, old friends. With some, I shared nostalgic reminiscences, with others a new conversation was begun-and then there were a few first-time encounters, adding spice to the experience. Among those, perhaps the freshest was that with Okshteyn, whose extremely large pencil rendering of a battered metal can bestows upon the subject, both a monumentality and a microscopic scrutiny that rattles back and forth between coldly observant and passionately loving.

___David Brickman, Let’s Go Pop, New York State Museum, Albany, NY Extra-Ordinary: The Everyday Object in American Art...

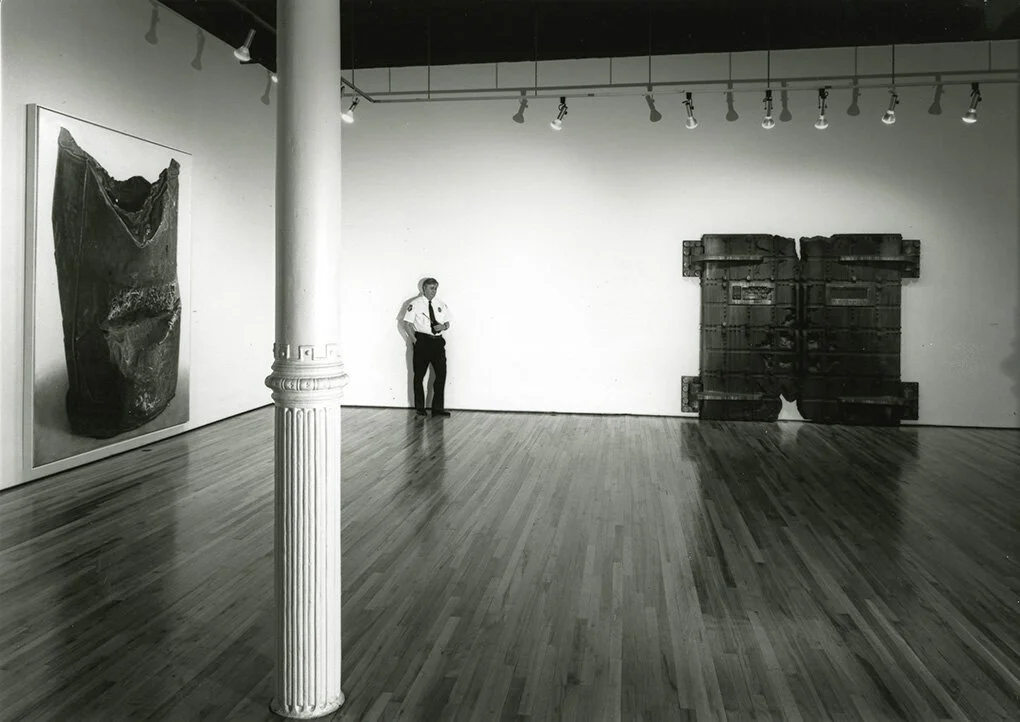

Installation view. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY, 2002-2003. Approaching Objects,Works from the permanent collection.

Works pictured: Shimon Okshteyn, Metal Container, 2000; Claes Oldenburg , Jeff Kons, Cristo.

Installation view: New York State Museum, Albany, NY, Selections From The Whitney Museum of American Art, 2005

Works pictured: Shimon Okshteyn, Metal Container, 2000; Louise Nevelson.

Mr. Okshteyn's large, grisaille photorealistic pictures are technically impressive, especially the ones made from graphite. But there is more than just craft at stake. Mournful images of an empty wheelchair, a hospital gurney, a collection of pills and bouquets of flowers tell an oblique story of illness and death.

__Ken Johnson, The New York Times, Art Guide

Okshteyn's works, whatever their medium, tread a fine line between representation and abstraction, veering more to the latter the closer one looks. The luminous, agitated gestures that mark the dark indentation in the middle of the can; the finely shaded detail of the rows of dots in the small paintings of the thimble; the strands of paint that hang from one comb like sticky hair, all the more startling because of the thick black field on which the comb rests like a mirage; the pinkness of the other comb, also startling because of the surrounding gray, as dense as the black, if differently textured; the obscured stencil lettering on the suitcase--all of this is the result of the emotional pressure that Okshteyn's touch puts on the physical object, transforming it into an abstract idol. The complications of his touch make it at once more particular — more physically miraculous--and more potently symbolic.

Okshteyn’s paintings are dreams into which we fall as though into a dangerous wishing well. Okshteyn’s paintings are dreams, in which reality is charged with hope as well as despair — charged with emotional depth and complexity we never truly experience except when we dream. It is the turbulent dreamy surface of Okshteyn’s paintings that show how much this battered object belongs to painful memory.

___Donald Kuspit. NYARTS

Okshteyn knows how to take play out of Pop, where much of his work is rooted. He renders it joyless and at the same time more personal than we’re accustomed to seeing.

__Barbara A. McAdam, ArtNews

Shimon Okshteyn’s monumental graphite drawing of a steam iron lends sculptural solemnity to a mundane appliance. It stands on its heel, a rubber cord coiled around its base like a decorative architrave of a plinth. A squat obelisk, Mr. Okshteyn’s iron takes on the poignance of Cleopatra’s Needle, scarred with the traces of time but still upright.

___ Maureen Mullarkey, The New York Sun, Here Is The Thing. Simple Thing, Katonah Museum of Art, NY

Ukranian-born artist Shimon Okshteyn lives and works in New York City and is well known for his technically brilliant still life drawings in pencil and charcoal. Recently, he has been including whimsical frames to accent his drawings, which contrast with the seriousness of his drawings. While making the glass frames, Okshteyn began making large scale sculptures in glass, which were included and sold in his most recent New York exhibition.

___Geof Isles, Glass Magazine

The royal Medici of Florence, Italy, earned a dubious place in posterity for their skill in poisoning family members. But a new exhibit suggests they were equally delighted to lavish their attention on family treasures already dead. ”Natura Morta”, a major touring show at the Memorial Art Gallery, displays 42 still lifes that reveal the lavish lifestyles and sometimes bizarre interests of these patrons.

….Or you could head for an irreverent sideshow by contemporary Ukranian-born artist Shimon Okshteyn. A back room features nine of his monochrome drawings based on 17-century still lifes. Okshteyn gleefully gets into the spirit of Medici excess. He takes their artists’ mania for detail and sends it way over the top. He encrusts his frames (and sometimes the canvases, too) with fake fruit, pink tassels and splotches of dripping paint. The ultimate in kitsch is his spoof of Filippo di Liagno’s Two Citrons (1618). He surrounds the yellow, nubby-skinned fruit with plastic babies in blue diapers and a statue of an embracing couple. “It may be about fertility”, speculates Hamann-Whitmore. Purists may not appreciate Okshteyn’s wry take on the art of the rich and powerful. But as the devilish Catherine de Medici might have remarked: One man’s meat is another man’s poison.

__Stuart Low, Rochester City Newspaper, Visual Arts, Larger Than Life, Memorial Art Gallery, “Natura Morta”, 42 still life paintings and mosaics collected by the Medici of Florence. Companion show “After Lifes: Recent Works by Shimon Okshteyn” Memorial Art Gallery, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY

Installation view: Memorial Art Gallery, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY, After Lifes: Recent Work by Shimon Okshteyn

Companion Show to Natura Morta: Still-Life Painting and the Medici Collections, 2007

Who says art is strictly for old fussies? It can be very frothy stuff, like this Shimon Okshteyn “fiberglass with marble dust” sculpture of a man jerking off his giant tool. I caught it on a high-minded jaunt to the Stefan Stux gallery the other night, so I gamely posed with it (captured by Brian Cummings), anxious to interact with a piece of art that’s THAT good. I even got to meet the artist, who admitted without prompting that he’s totally the basis for the sculpture. “Hmm, nice dick,” I remarked with my usual intellectual appreciation, slyly glancing downwards. He half smiled. And somehow the art world will never be the same.

___Michael Musto, The Village Voice, Chelsea Gallery Shows Quite A Piece!

Many of Okshteyn’s works betray tongue-in-cheek mischievousness, but they are also poignant meditations on time, aging, and mortality.

___Francine Koslow Miller, Arforum.com, Critics’ Picks

Shimon Okshteyn’s visual world is unusually bracing because its fastidious craftsmanship, strong compositional formats and unusual mixtures of materials leads us to an inner world whose range is as complex as it is unpredictable and varied. In other words what we have here is a sophisticated and ultimately mature art form that expresses and exposes in equal measure. Okshteyn is a force to contend with. His well-informed appropriationist tendencies are abetted by the artist’s urge towards classical traditions that balance gloomy introspection against outward looking strength. Add to this a coherent yet surprising use of thematic material, a richness of invention, and systematized build up of narrative — all of these aspects make Okshteyn’s work irresistibly attractive to the eye —a haptic feast laced with megatonic power.

___Dominique Nahas, New York City

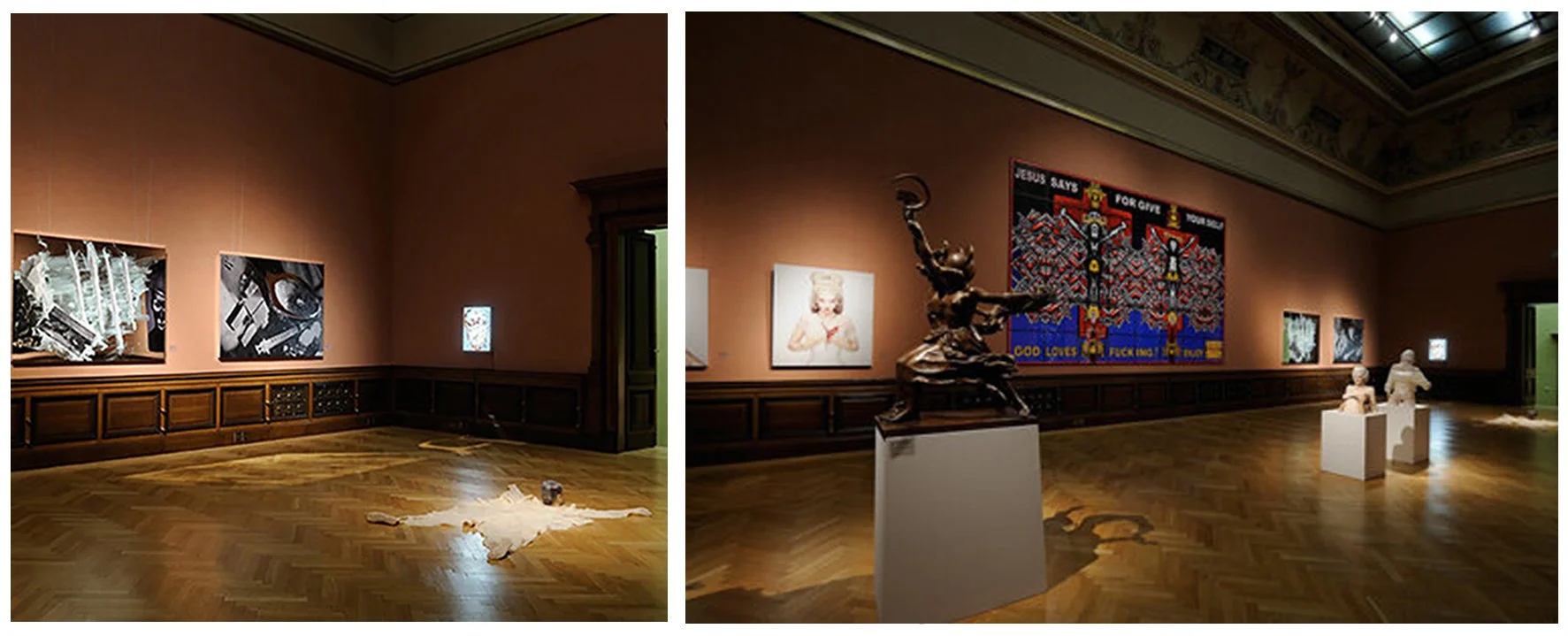

Installation view: Museum of Decorative Arts, Prague, Czech Republic, Decadence Now! Visions of Excess, 2010 - 2011

Works pictured: Shimon Okshteyn, Cocaine, 2008 and Spoon, 2008; Jeff Koons, Cindy Sherman, Jake and Dinos Chapman, Gilbert and George.

In 1980, Shimon moved to America and his artistic career took on a new turn, influenced by New York and Americana, based on the "American Reality" concept. Innovation of form, an original use of color, themes, and all items that take part in the conceptual and artistic innovations of the work, allow us to state that Shimon Okshteyn is one of the greatest living artists.

Using different techniques allows Shimon Okshteyn to generate rich and complex surfaces, where collage has a lion's share. A work is often designed as a huge pattern where each item is adjusted against another to build an image. Neighborly relationships participate in a new visual unity and semantic meaning of the work.

Woman is the dominant figure, provocative, even sexy, however only in appearance. As a matter of fact, if our perceptions are disturbed by Okshteyn's faces, it could well be because they refer directly to the precariousness of our lives, repeatedly alluding to the futility of our pleasures, our joys, our pains, our sadness, our life, our world?

___Jean-Pierre Garand , Art Historian

Through the windows in his studio, I see the tall trees of the forest surrounding his house. I recall him telling me, almost confessionally, that for an artist not the least bit interested in landscapes, he suddenly noticed an arresting tree formation near his home, and the next thing he knew he had embarked on Hamptons Landscapes 1-5 (photographs with oil paint and enamel, 73/4 x 5 5/8 inches), Southampton Polo (60 x 80 x 24 inches, oil on canvas with umbrella) and Hamptons Landscape (oil on canvas with collaged reeds, 53 x 69.5 inches).

All of these were selected for the exhibition, and Lehr was no doubt keen to showcase them, not just as a new moment in Okshteyn's broad oeuvre, but also as a point of connection to so many other art world luminaries who have lived in the area and, at some point or another, been seduced by its natural beauty.

___Kelcey Edwards, Larger Than Life: A Journey Through Shimon Okshteyn’s Art That Skewers and Reveals Hamptonsarthub.com

I cannot remember how or when I met Shimon Okshteyn — I can only remember thinking that I couldn’t believe I didn’t know about him already. His work made an indelible impression on me. From his incredible oil paintings to his amazing drawings of thimbles, typewriters, and other common items, they were made very uncommon by his genius.

___ Paton Miller, artist and curator, Southampton, NY

Shimon Okshteyn (1951–2020) was a Ukrainian artist born in the city of Chernivtsi. He graduated from the Mitrofan Grekov Art College in Odessa, Ukraine, and has lived and worked in the USA since 1980. It was there that Okshteyn keenly but sensitively observed the environment in which he found himself. He did not cling to the past, but took the best from it. In his work, he used various art historical references, such as elements from the Renaissance, Baroque, social realism or German expressionism, which he sensitively connected with the present. In this way, he created his own reality, in which he focused on the tension between high and low, public and private, abstraction and figuration.

____ Otto M. Urban, Curator, Czech Republic, 2024